How Identity Binds and Blinds

Our identities play a role in how we interact with each other.

“Faced with the choice between changing one's mind and proving that there is no need to do so, almost everybody gets busy on the proof.”

― John Kenneth Galbraith

In a short essay, tech investor Paul Graham writes about how some conversations or debates degenerate into defensive discussions, making it impossible to find good ideas and solutions. He uses the example of how political arguments become religious, and therefore no progress is made.

However, he puts forward the argument that the problem isn’t politics itself. Instead, pulling from his own experience in technology, which can also become defensive because people identify with specific programming languages, he points out that the problem is with identity.

His conclusion is; “If people can't think clearly about anything that has become part of their identity, then all other things being equal, the best plan is to let as few things into your identity as possible."

Is limiting the things you identify with the only solution? Are there other ways we can productively discuss subjects people care deeply about? To understand these questions better, we have to look at how our minds work, which provides insight into the problem and some possible solutions.

Identity

Each person’s identity is complex. Definitions can range from physical attributes and characteristics to how we think of ourselves. Social Psychologist Ziva Kunda, who wrote Social Cognition: Making Sense of People, uses the term “The Self” to describe what most people would consider identity.

“When we use the term self, we have many meanings in mind. My self is the person I am now, the child I once was, the elderly person I expect to become. My self is the person who is my parents’ child, my children’s parent, my spouse’s partner, my co-workers’ colleague. My self is the center of my thoughts, feelings, desires, and actions. My self is the part of me which attempts to control my own thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and circumstances and also tries to manage other people’s impressions of me.”

Values are a cohesive foundation for our identities. Values define who we are because the things we think are important will greatly influence our beliefs, motivations, and actions. We spend time doing the things we value, and the more this happens, the more evidence our minds have to reinforce that identity.

We are also protective of our identities. We want to maintain our sense of self. So when confronted with something that threatens our identity, our goals and motivations focus on avoiding that loss.

Choosing what to value is important, but limiting what we identify with may not be a good idea. Participating in other groups that help diversify our identity can be helpful psychologically.

A study was conducted to test the relation between complex identities and stress. Candidates were asked to create meaningful groups that described aspects of their lives. For example, people would use groupings such as roles, relationships, activities, best qualities, etc.

They were then asked to write down a list of stressors in the previous two weeks and take a well-being test. Researchers found that among those with many stressors, the ones that had more groupings to describe themselves were less vulnerable.

So Graham is correct that our identities make it difficult to find real solutions and ideas if we perceive they are being threatened. However, there is evidence to suggest that instead of limiting what we identify with, a better solution is being more mindful of what we identify with.

The Righteous Mind

Someone who has taken a substantial “crack” at Graham’s question is Psychologist Jonathan Haidt. In his book The Righteous Mind, he identifies some key reasons we see Graham’s observation.

He re-enforces the broad psychological research that shows how our reasoning serves our beliefs and intuitions. Stating that our beliefs are post hoc constructions designed to justify our actions or support the groups we belong to.

He describes that our brain naturally functions more like a politician, looking for votes to support its position instead of a scientist looking for the truth. As objective as we may believe ourselves to be, our minds aren’t as rational as we think.

Ziva Kunda uses the term "Directional Goals," which is the tendency to find arguments in favor of conclusions we want to believe to be stronger than arguments for conclusions we do not want to believe.

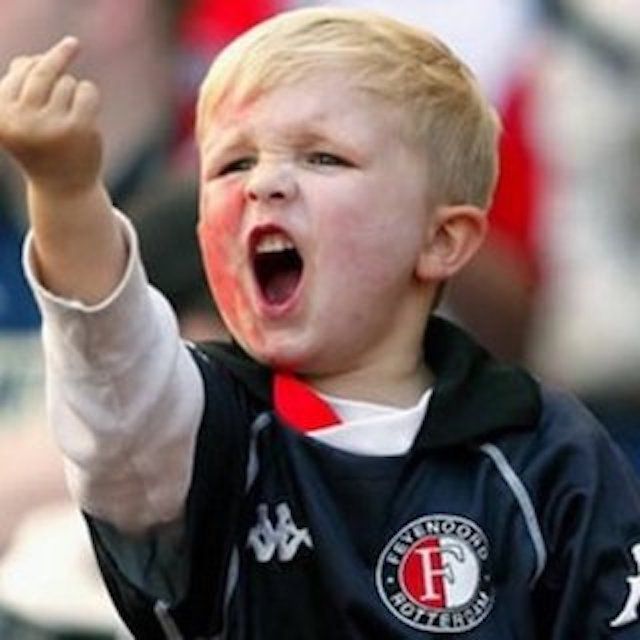

Haidt also explains how important group identity is. He thinks of it as a “hive switch” (representing the collective nature of a beehive) that activates neurologically. At times we can almost lose ourselves to the group identity.

Group identities have been studied by biologists, psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and pretty much anyone who wants to understand why people act the way they do. While they may differ in their explanations for why we form groups, it’s pretty well understood that groups are an essential part of our identity and something that we need.

Our minds look for certainty and order in a chaotic world. Similarities give us security, which is why we like to be members of groups with similar individuals. According to Social Identity Theory, we see ourselves as members of a group by supporting the group we are in or attacking other “out” groups. This is a natural cognitive process, and we do this to enhance our self-esteem and self-image.

So what's the solution?

Haidt argues we are more similar than different despite what we initially think. Most people have similar values to those in other groups but struggle to see them due to our natural process of seeking negative aspects in "rival" groups.

His advice isn’t to minimize your identity but instead utilize the fact that we all have multiple things we identify with. Going back to Kunda's example, our identities are complex and consist of many aspects of our lives.

Haidt says some of this happens naturally when you build relationships. He uses the example that politicians were less partisan when they all lived in D.C., which forced them to spend time together as they attended school events for their children and weekend functions.

Or, as Abraham Lincoln said, "I don’t like that man. I must get to know him better.”

Fighting Mental Biases

Is it possible for our minds not to be so biased?

By articulating opposing viewpoints voluntarily, we can look at other viewpoints more favorably. Studies have shown that when students write a paper or argue a viewpoint they disagree with, they will soften their opinion and view it more favorably.

Also, by applying the proper framework, our minds can be primed to focus on solutions. Research also shows that when people know they will be rated on the accuracy of their conclusions or asked to explain their reasoning, they rely less on biases and more on accuracy.

Kunda explains; “The work on accuracy-driven reasoning suggests that when people are motivated to be accurate, they expend more cognitive effort on issue-related reasoning, attend to relevant information more carefully, and process it more deeply, often using more complex rules.”

This is achieved by giving people “skin in the game.”

Kunda writes, “Accuracy goals are typically created by increasing the stakes involved in making a wrong judgment or in drawing the wrong conclusion, without increasing the attractiveness of any particular conclusion. The key strategy used to demonstrate that accuracy motives lead to more deep and careful cognitive processing involves showing that manipulations designed to increase accuracy motives lead to an elimination or reduction of cognitive biases.”

Conclusion

It’s fair to say that our identities and natural cognitive processes create obstacles to discussing issues that involve identities. This isn’t limited to politics but can also happen in workplace environments, family gatherings, and just about anywhere.

That being said, there are some ways that we can utilize our understanding of ourselves to work past some of these barriers. Of course, anything that has to do with how the brain works is complicated, so there won’t be an easy answer - But there are some principles to strive toward.

Footnotes

- Keep Your identity Small Paul Graham

- The Righteous Mind Jonathan Haidt

- The Case for Motivated Reasoning Ziva Kunda

- Self-Complexity as a Cognitive Buffer Against Stress-Related Illness and Depression Patricia W. Linville

- Values as the Core of Personal Identity: Drawing Links between Two Theories of Self Steven Hitlin

- Social Cognition: Making Sense of People Ziva Kunda

- Social Identity Theory Summary

- Nassim Taleb wrote a book called Skin in the Game to expand on that concept.