How to Find Ideas That Work

Finding good ideas requires testing out lots of bad ones.

In the small village of Menlo Park, on New Year's Eve 1879, men and women dressed up in elegant evening attire stepped off the nighttime train to see for the first time, a series of gleaming lights.

People from all over came to see the first public demonstration of Thomas Edison's newest invention. The incandescent light bulb would revolutionize daily life for most Americans who at the time, relied on candles and kerosene for light.

While Edison gets credit for inventing the light bulb in 1879, the reality is, more than 20 other creators patented similar ideas in earlier decades, the first being in 1841. But numerous inventors failed to produce a safe, bright, and affordable light bulb that could stay lit for more than a few minutes.

Edison had created a system that would find practical solutions where others failed. In addition to the light bulb, he invented the automatic telegraph, carbon telephone transmitter, phonograph, the movie camera, and alkaline storage battery in his lifetime.

Edison was able to tap into something that helped him become one of the most prolific inventors of all time. Being able to understand those incites can help people create better solutions and improve their chances of achieving their goals.

We all have ideas, but how do some find success when so many never make it past living room conversations? In this article, we will look at some insights and strategies that might reframe the way you think about finding the perfect idea, making progress, and discovering what works.

Classroom Experiment

In the book Atomic Habits, James Clear writes about an art teacher who divided his students into two groups on the first day of class.

The first group would be in the "quantity" group, which meant they would be graded on the amount of work they produced. On the final day of class, the teacher would tally the number of photos submitted by each student. One hundred photos would get an A, ninety photos a B, eighty photos a C, and so on.

The second group would be in the "quality" group. They would be graded only on the excellence of their work. They would only need to produce one photo during the semester, but it had to be a nearly perfect image to get an A.

At the end of the term, the teacher was surprised to find that the "quantity" group produced all the best photos.

Why?

During the semester, these students were busy taking lots of photos. They ended up spending their time experimenting, testing out various methods, and learning from their mistakes.

In creating hundreds of photos, they improved their skills while the quality group spent their time thinking about - but not testing - what made the perfect photo. The striving for perfection, instead of repetitions, limited their development and execution of their ideas.

Programming Puzzle

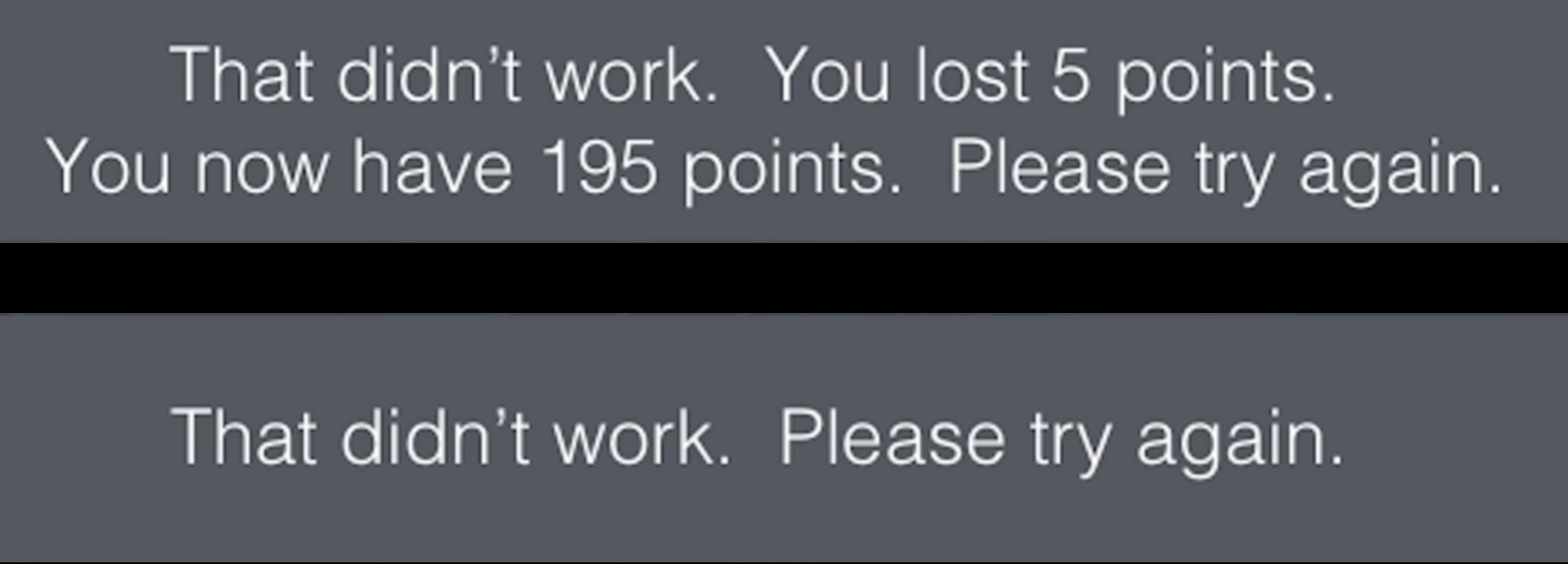

Former NASA engineer Mark Rober invited his YouTube audience to participate in an introductory programming puzzle. In this challenge, the participants solved a puzzle by putting together the correct sequence of commands. Both groups were given 200 "points" to start.

But the participants didn't know that there were two different versions of the puzzle, each giving a different message when they failed.

In one group, when they entered the wrong sequence, they were given the message, "That didn't work. You lost 5 points. You now have 195 points. Please try again."

When the second group entered the wrong sequence, they were given the message "That didn't work, please try again." There was no mention of any loss of points.

Here are the results from the 50,000 people who decided to take the challenge:

- Only 52% of the people who were told they lost points completed the puzzle correctly.

- While 68% of the people whose message didn't mention lost points completed the puzzle correctly.

What was the biggest reason for the second group's success? They attempted to solve the puzzle 2.5 times more than the people who were told they would lose their imaginary "points."

Little Bets

In the book Little Bets by Peter Sims, the author writes about how Chris Rock develops his comedy routines. First, he visits small comedy clubs to try out rough, untested material. Whether they succeed or fall flat, these raw, new jokes are what the author calls "little bets," which are guideposts that give him creative direction.

We tend only to see the final product of successful people, just like we would if we watched a Chris Rock special once it has been perfected. But, unfortunately, only seeing the final product without seeing the messy previous versions that led up to it can give the impression that only some people have special abilities.

But the truth is many successful people don't burst on the scene with new ideas all at once. Instead, they use incremental, trial and error methods to see what works and improve their ideas. They recognize that - they don't know what they don't know - and taking little bets allows them to try out and build onto creative thoughts and concepts. They give them experience that can be used as a foundation for reaching their goals.

The quicker and more frequently you make errors, the faster your mind is cued to error correction. As a result, you will become more alert and primed to recognize and learn solutions. Once you finally get it right, your brain will identify patterns of what works.

Embracing Failure

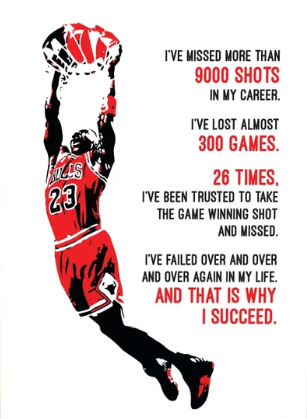

Growing up, I had a poster that contained more wisdom than I realized at the time. Wisdom that gave some insight into how to get better at something. Was it some wise philosopher? No, it was his Airness Michael Jordan, and he says;

"I've missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times I've been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed."

Even Thomas Edison had many failures. He spent part of his life convinced he could revolutionize the mining industry, becoming obsessed with building a massive facility that was such a failure it became known as "Edison's folly."

But he would apply the lessons from that failure to a cement manufacturing venture that eventually became one of his most profitable investments and even supply the cement for Yankee Stadium.

During his lifetime, Edison received 1,093 U.S. patents: 389 for electric light and power, 195 for the phonograph, 150 for the telegraph, 141 for storage batteries, and 34 for the telephone. But he also filed an additional 500 to 600 that were unsuccessful or abandoned.

And how was he able to find a practical solution that would eventually put lights in every house in America? Edison and his assistants tested more than 6,000 materials before finding one that worked.

Finding what works can be difficult because of the world's unpredictability and people's tendencies to avoid trying out their ideas. Many factors have to come into play for something to actually pay off, too many for us to comprehend.

So the strategy? Stop worrying about being perfect and start putting ideas out there to see what gains traction. Allow failure to guide your process of improving your ideas to something that works.

Sources

- The Super Mario Effect - Tricking Your Brain into Learning More by Mark Robe

- When Edison Turned Night into Day by Christoper Klein

- 6 Key Inventions by Thomas Edison by Patrick J. Kiger

- The Practical Incandescent Light Bulb Edison Museum

- Edisons Big Failure by John H Lienhard

- Atomic Habits by James Clear

- Little Bets by Peter Sims