5 Keys to Mastery and Long Term Fulfillment

Finding enjoyment in between where we are and where we want to be is key to long-term fulfillment.

Pay attention to the messaging that is dominant in our modern world. We are continually bombarded with promises of immediate gratification, instant success, and fast, temporary relief.

Get rich quick gurus, crash diets, and miracle drugs stem from our worship of quick, effortless success and fulfillment. Instagram is one fake fantasy crowded out by the next.

These patterns we consume make our expectations of improvement and achievement unrealistic. And when reality doesn't match expectations, we get discouraged, give up, and limit our potential for growth.

Archetypes

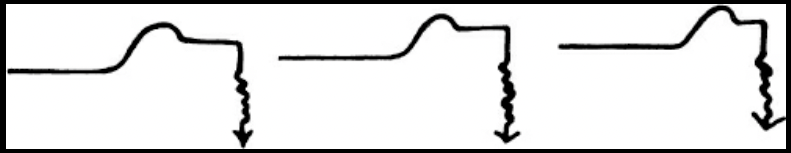

George Leonard, Aikido blackbelt and author of Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment, writes about three common archetypes he finds that most people fall into when trying to achieve their goals.

- The Dabbler - approaches new sports, careers, or relationships with enthusiasm. They are thrilled at first and love the ritual of getting started, the spiffy equipment, and the shine of newness. But when they hit a plateau, they get discouraged, and their enthusiasm wanes; this is when they start looking for something different.

- The Obsessive - is a bottom-line type of person, not settling for second best. They know results count, and it doesn't matter how you get them, just that you get them fast. They don't accept plateaus and keep pushing hard until they have a sharp decline and crash.

- The Hacker - Looks for learning opportunities but settles. After getting the hang of things, the hacker is willing to stay on the plateau indefinitely.

Our brains are wired to pursue

Our brains are naturally wired to pursue goals and novelty.

Our dopamine systems evolved in our ancestors, at a time of extreme scarcity, as motivation to pursue things that would keep them alive. But today, there are plenty of ways you can seek "quick fixes" and distractions to supplement your drive for dopamine.

When you seek novelty and dopamine hits too often, it takes more and more to enjoy it over time, leading to long-term motivation problems and burnout. That's why over time, your excitement drops.

But on the flip side, only concentrating on results, with nothing in between, slows down your mind's perception of time. When you only focus on outcomes, you undermine the importance of the process in your mind, making the experience less enjoyable and even painful.

This is because so much of our desire for something is motivation to reduce pain when we don't have it. But dopamine isn't the only reward system we have.

Life is in the middle

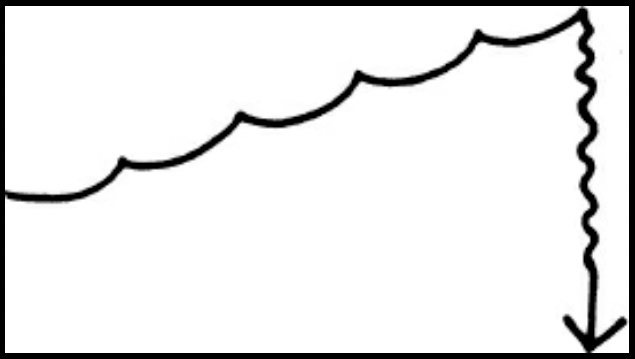

Real improvement in anything involves learning, and learning something to the point of progress takes time and effort.

Our nervous systems are very stable (which is good), but for that stability to be maintained, it must carefully manage the amount of change before the brain is rewired and change is made automatic.

So learning any new skill involves brief spurts of progress, each followed by a slight decline to a plateau somewhat higher in most cases than that which preceded it.

Performance expert Anders Ericsson writes;

"Whenever you're trying to improve at something, you will run into such obstacles—points at which it seems impossible to progress, or at least where you have no idea what you should do in order to improve. This is natural. What is not natural is a true dead-stop obstacle, one that is impossible to get around, over, or through. In all of my years of research, I have found it is surprisingly rare to get clear evidence in any field that a person has reached some immutable limit on performance. Instead, I've found that people more often just give up and stop trying to improve."

This learning pattern means that, in the pursuit of any goal or skill acquisition, most of the time you spend will be in between milestones. And when you only focus on the peaks instead of the valleys, you waste a lot of your life because most of your life will be spent in the middle.

So how can you find the necessary motivation to stick with achieving our goals?

Leonard says you have to focus on Mastery.

Mastery

Daniel Chambliss, a professor of Sociology, researched the nature and satisfaction of athletes who pushed themselves to excellence. He interviewed and studied 120 world-class swimmers and coaches.

He concluded that one of the main differences that separated top performers from others was their attitude toward what most found difficult:

“At the higher levels of competitive swimming, something like an inversion of attitude takes place. The very features of the sport that the ‘C' swimmer finds unpleasant, the top-level swimmer enjoys.

What others see as boring - swimming back and forth over a black line for two hours, say - they find peaceful, even meditative, often challenging, or therapeutic. They enjoy hard practices, look forward to difficult competitions, try to set difficult goals.

Coming into the 5:30 A.M. practices at Mission Viejo, many of the swimmers were lively, laughing, talking, enjoying themselves, perhaps appreciating the fact that most people would positively hate doing it.

It is incorrect to believe that top athletes suffer great sacrifices to achieve their goals. Often, they don’t see what they do as sacrificial at all. They like it."

Lieberman and Long, authors of the Molecule of More describe Mastery as the pleasure of being good at something for the sake of itself. Its ability to extract the maximum reward from a particular set of circumstances.

They write that to enjoy the things we have vs. what is possible; our brains have to transition from future-oriented dopamine to present-oriented chemicals, a collection of neurotransmitters called "Here and Now" Molecules."

These molecules allow us to find satisfaction in what our senses deliver, what is right in front of us, and what we can experience without a nagging feeling that we need something more.

This is an example of what Leonard focuses on in pursuit of Mastery. He writes, "Actually, the essence of boredom is to be found in the obsessive search for novelty. Satisfaction lies in mindful repetition, the discovery of endless richness in subtle variations on familiar themes."

He believes that the master's journey can begin whenever you decide to learn any new skill, hobby, or profession, but you don't approach it in the traditional sense. "It achieves a special poignancy, a quality akin to poetry or drama, in the field of sports, where muscles, mind, and spirit come together in graceful and purposive movements through time and space."

So what does this look like? Leonard gives 5 Keys to Mastery.

5 Keys to Mastery

Instruction

"There are some skills you can learn on your own, and some you can try to learn, but if you intend to take the journey of mastery, the best thing you can do is to arrange for first-rate instruction."

Some things you can learn on your own, through reading books or searching for information online. But Leonard believes there's nothing better than being in the hands of a master teacher, either one-to-one or in a small group.

Anders Ericsson agrees that the best way to get past any barriers is to come at it from a different direction, which a teacher or coach can help with. You want to find someone already familiar with the sorts of obstacles you're likely to encounter and can suggest ways to overcome them.

But Leonard advises that you have to focus not only on credentials but also on working with people. "Knowledge, expertise, technical skill, and credentials are important, but without the patience and empathy that goes with teaching beginners, these merits are as nothing."

Practice

"There's another secret: The people we know as masters don't devote themselves to their particular skill just to get better at it. The truth is, they love to practice—and because of this they do get better. And then, to complete the circle, the better they get the more they enjoy performing the basic moves over and over again."

Larry Bird was one of the most complete basketball players of all time, primarily due to his dedication to practice. But, according to his agent Bob Wolf, Bird didn't just practice for the accolades, "He does it just to enjoy himself. Not to make money, to get acclaim, to gain stature. He just loves to play basketball."

Most people practice to learn a skill, but for someone on the master's journey, practice is not something you do but is something you have, something you are. Leonard compares it to the Chinese word tao and the Japanese word do, which means, literally, road or path. Practice is the path upon which you travel.

Surrender

"The courage of a master is measured by his or her willingness to surrender. This means surrendering to your teacher and to the demands of your discipline. It also means surrendering your own hard-won proficiency from time to time in order to reach a higher or different level of proficiency."

If you want to grow, there are times when it becomes necessary to give up some hard-won competence to advance to the next stage.

Your brain learns when you put yourself in situations where you make mistakes, giving you heightened awareness and focus. So if you leverage frustration to dig deeper and keep going, you are setting yourself up for plasticity (change) mechanisms to engage.

But to do so, you have to allow yourself the freedom to make mistakes and feel clumsy. If your ego is too rigid, you won't let yourself go through the natural learning process.

Intentionality

"It joins old words with new—character, willpower, attitude, imaging, the mental game—but what I'm calling intentionality, however you look at it, is an essential to take along on the master's journey."

"All I know," said Arnold Schwarzenneger, "is that the first step is to create the vision because when you see the vision there—the beautiful vision—that creates the 'want power.' For example, my wanting to be Mr. Universe came about because I saw myself so clearly, being up there on the stage and winning."

The first step to increasing your brain's learning capacity is recognizing you want to change something by bringing it to your consciousness. Then, the additional focus triggers mechanisms that will help you learn.

Improving performance goes hand in hand with improving mental representations. As one's performance improves, the representations become more detailed and effective, making it possible to improve even more.

Peter Senge, Author of the 5th Discipline, writes that there are two fundamental sources of motivation - fear and aspiration. Creating a vision is the picture of the future you wish to create.

The Edge

"Almost without exception, those we know as masters are dedicated to the fundamentals of their calling. They are zealots of practice, connoisseurs of the small, incremental step. At the same time—and here's the paradox—these people, these masters, are precisely the ones who are likely to challenge previous limits, to take risks for the sake of higher performance, and even to become obsessive at times in that pursuit. Clearly, for them the key is not either/or, it's both/and."

Anders Ericsson says that the best form of practice requires you to try things that are just beyond your current abilities constantly. And sometimes, right outside your comfort zone involves risk.

Leonard writes, "Playing the edge is a balancing act. It demands the awareness to know when you're pushing yourself beyond safe limits. In this awareness, the man or woman on the path of Mastery sometimes makes a conscious decision to do just that."

Conclusion

According to Leonard, Mastery is needed in our modern world and brings a different perspective toward improvement and achieving goals. It's a long, difficult journey, but it also brings fulfillment and meaning. It's the ultimate human adventure.

"It resists definition yet can be instantly recognized. It comes in many varieties, yet follows certain unchanging laws. It brings rich rewards, yet is not really a goal or a destination but rather a process, a journey. We call this journey mastery, and tend to assume that it requires a special ticket available only to those born with exceptional abilities. But mastery isn’t reserved for the supertalented or even for those who are fortunate enough to have gotten an early start. It’s available to anyone who is willing to get on the path and stay on it—regardless of age, sex, or previous experience."

Sources:

- Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long Term Fulfillment by George Leonard

- Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity―and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race by Daniel Lieberman and Michael Long

- The Mundanity of Excellence Daniel Chambliss