How Managing This Molecule Can Help You Achieve Your Goals

Neurochemistry can play a big role in maintaining motivation.

Every year in January, people make their new year's resolutions with well-intentioned goals to improve their lives. But, unfortunately, depending on what poll or study you find online, around 80% of people quit before achieving them.

Why do most of these plans fall apart? As Mike Tyson eloquently says, "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face."

That punch in the face typically causes people to give up, either because they lose interest or burn out. Both are problems of motivation. Not motivation as in willpower - biological motivation. Our motivation comes from a tiny molecule that has shaped the course of human evolution.

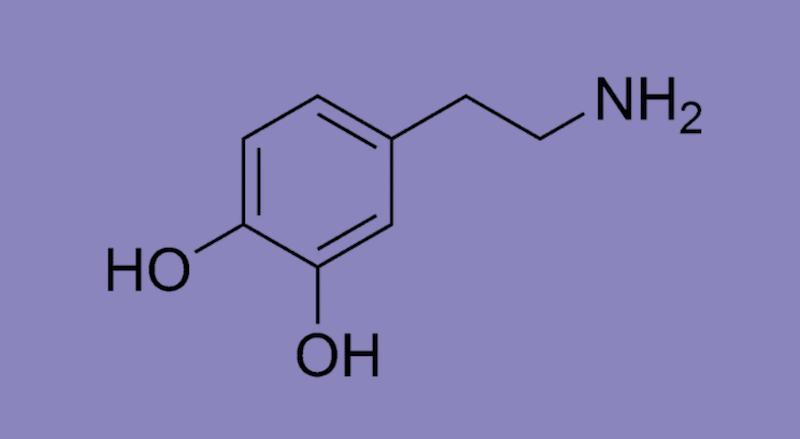

That molecule is Dopamine.

Dopamine is a neuromodulator, which means it influences the coordination of many circuits. Dopamine moves us toward our goals and helps us track success. It's responsible for drive and craving. It's the primary determinant of how motivated we are.

For example, in experiments in mice, when deprived of Dopamine, they wouldn't move even a few inches to get food. The same effect happens in humans who have conditions that limit their dopamine release.

According to authors Daniel Lieberman and Michal Long, who wrote The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race, no creature on earth has as much Dopamine as humans. It's one of the main things that makes us different and gives us our ability to accomplish so much but can also give us problems if not managed correctly.

While there are certainly people with actual health conditions that inhibit motivation, for the rest of us, one problem is not understanding how to manage Dopamine toward healthy pursuits.

Neuroscientist Andrew Huberman says a key to a healthy life is intermittent Dopamine release toward positive behavior. Thus, finding the balance between pleasure and pain.

Besides some biological factors (food, reproduction, etc.), Dopamine doesn't care what your goals are, just that you achieve them. So there are ways that you can create a more sustainable, organic, and effective plan toward achieving your goals through proper management of your dopaminergic system.

What Goes Up, Must Come Down

So how can our dopaminergic levels be mismanaged?

Everyone has baseline Dopamine levels, which is the consistent release your body needs to move into action every day. But some things give us bigger hits of Dopamine which are mainly used to motivate us toward goals that we are biologically wired for or goals that we think are important.

Huberman says that Dopamine is the currency for seeking and foraging. These dopamine systems evolved in our ancestors as motivation to pursue things that would keep them alive.

Imagine you lived among our hunter-gatherer ancestors. While searching for food, your brain starts to release higher dopamine levels in anticipation of finding food to keep you motivated. As soon as you find what you were looking for (food), your brain gives you a much larger release of Dopamine to reward you for achieving your goal.

After achieving your goal and using Dopamine, your reserves would be depleted from finding food. This would cause you to lose motivation from searching for food for a short time.

Think of it like a gas tank; whatever fuel you used to get to the store, you don't have until you fill back up. So your crash is directly related to how much you used. The bigger the peek, the harder the crash.

This is why after a big win or accomplishment, you can feel down the next day. You feel the result of not having as much Dopamine to operate with since it takes time for your reserves to build back up - to put more gas in the tank.

So Dopamine is a double-edged sword.

Let's say that while your reserves were building back up, you experienced something else that would typically give you a big boost of Dopamine. You wouldn't experience as much joy because you have less in reserves as if you were back to baseline. So how satisfying something is, depends on the peak compared to the baseline.

Each time you experience something, your pleasure response decreases, and your pain response increases. That's why over time, our excitement drops. When you stack multiple Dopamine, including activities to get you excited for something, it takes more and more to get you to enjoy it over time. Trying to increase Dopamine too often or too consistently can lead to long-term motivation problems and burnout.

Focusing on only a reward slows down our perception of time. If you've ever been in line for TSA and you have a flight to catch, you know what this feels like. When reward only comes at the end, you undermine the process, making that experience less enjoyable and even painful over time. This is because so much of our desire for something is motivation to reduce pain when we don't have it.

So how can we avoid mismanagement of Dopamine in pursuit of our goals? We will cover three different principles: Intermittent dopamine release, internal motivation, and focusing on the "Here and Now."

Intermittent Dopamine Release

Behaviorist B.F. Skinner, one of the most influential psychologists and pioneers of behaviorism, conducted experiments in the 1960s to understand what motivates our behaviors.

He placed pigeons in a box and trained them to peck at a lever whenever they wanted food. He found that if the number of times needed to hit the lever was predictable, the pigeons would peck unenthusiastically until they received their reward.

However, as soon as he set the food to be released randomly and the pigeon didn't know how many times it needed to hit the lever, they got excited, and their pecking rate increased. This knowledge has since been used to build places like Las Vegas, where even when everyone knows the house always wins, the fact that you MIGHT win keeps you going back.

This is because novelty and surprise is a stimulus for our Dopamine systems. Dopamine loves the anticipation of reward and motivates us more consistently than a fixed reward. Back in our evolutionary past, when hunting or searching for food, they weren't guaranteed to achieve their goal. Therefore, our brains evolved to crave the chance or anticipation of reward.

Instead of rewarding yourself every time you progress toward your goal, reward yourself randomly to take advantage of surprise. For example, download an app that rolls dice or even flip a coin to decide if you will give yourself something extra.

Break up your goal into smaller milestones so you aren't only focused on one primary result. But when moving toward goals, you should blunt some rewards. Learning to be comfortable with occasionally not rewarding yourself will help maintain your reserves for the long run. While counterintuitive, it can be helpful not to celebrate every win.

Internal vs. External Motivation

Psychologists Mark Lepper, David Greene, and Richard Nisbett were interested in testing the effects of external rewards on children. All children selected for their experiment were interested in drawing. Lepper, Greene, and Nisbett wanted to see what effect introducing rewards would have on their motivation toward an activity they already enjoyed.

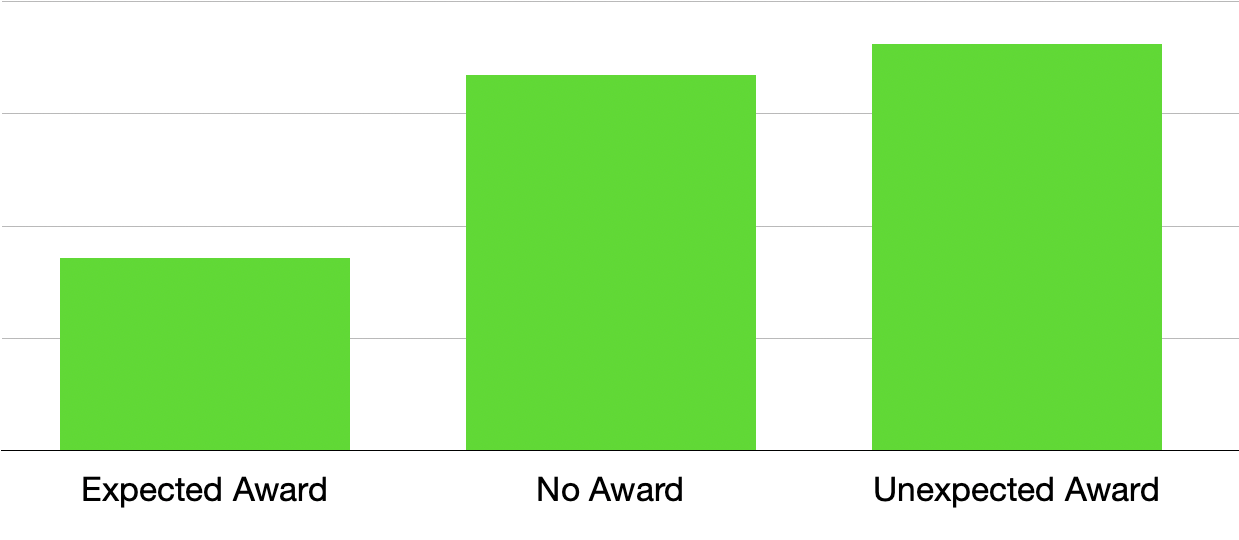

The children were split into three different groups and were instructed to draw. Each group had different reward systems.

- Expected Award - This group was told they would be given an award and received one after completion.

- No Award - This group was not told about an award and did not receive an award after completion.

- Unexpected Award - This group was not promised an award but was surprised with an unexpected award after completion.

Over a few days, the children were observed to see how much they would continue drawing of their own. Which group do you think drew most?

You probably correctly guessed that the unexpected award would motivate children to draw the most if you read the first section. But what might be surprising is that the group that received no promise or award drew more than the expected award. They weren't too far off from the unexpected reward group.

When you receive a reward for doing a task, your mind interprets that you didn't do an activity for an activity; you did it for the reward. Therefore, making the work much more challenging because your brain isn't rewarding you for the activity itself. Why would it? It's not the goal.

The challenge then is to learn to access rewards from doing and effort. While it won't be easy at first, as soon as you recognize discomfort or little motivation from doing a strenuous activity to pursue your goal, remind yourself about the benefits of what you are doing.

If you have a goal of losing weight, for example, every time you workout, you won't lose weight in the moment, but you are doing something that day that's improving your health. Reminding yourself of the benefits of what you're doing can help you generate rewards for doing that behavior.

We can reframe our experience and find ways to pull any and every benefit from the process. For example, former Navy Seal Jocko Willink is known for his motivational approach to difficult situations, which is essentially an awesome way of finding the silver lining in every experience.

Here and Now

Dopamine is necessary for anticipation and motivation, but it isn't required for enjoyment or pleasure.

Lieberman and Long write in their book that to enjoy the things we have vs. what is possible; our brains have to transition from future-oriented Dopamine to present-oriented chemicals - a collection of neurotransmitters called "Here and Now" Molecules."

Dopamine is about change, designed to motivate us for action, but by nature, it encourages dissatisfaction while "Here and Now" molecules are about enjoying reality.

We have other chemicals that give us pleasure from sensation and emotion, such as serotonin and oxytocin, to name a few. These molecules allow us to find satisfaction in what our senses deliver, what is right in front of us, and what we can experience without a nagging feeling that we need something more.

The authors write that they can work together, but under most circumstances, they counter each other. When "Here and Now" molecules are activated, Dopamine is suppressed, and when Dopamine is activated, "Here and Now" molecules are suppressed. Using both Dopamine and our "Here and Now" molecules, we can achieve harmony in pursuing our goals.

How do we do this?

Concentrating on the here and now forces us to spend time in the present. Catch your mind when it starts to drift to pay attention to something specific. One beneficial tool is deliberate practice.

Anders Ericsson, a performance expert, and psychologist writes that one of the traits of deliberate practice is full attention and conscious action. You have to concentrate on a specific goal for that session, making tiny adjustments when you veer from your intended target. An example would be shooting 100 basketball shots vs. shooting 100 basketball shots WHILE focusing intensely on your form.

Ericsson writes that the satisfaction of seeing yourself improve can be a massive difference in whether a person will maintain the consistent effort necessary to achieve your goals.

This type of focus improves what Lieberman and Long call "Mastery," which is the pleasure of being good at something for the sake of the thing itself. It's the ability to extract the maximum reward from a set of particular circumstances. This gives us satisfaction and contentment with the time we are spending improving in-between achieving our goal.

Peter Senge, Author of The Fifth Discipline writes that mastery becomes a discipline, an activity we integrate into our lives. We continually clarify what is important to us by working toward mastery and continuously learning how to see current reality more clearly.

So while trying to achieve your ultimate goal, work toward achieving some level of mastery in the activity itself.

By finding balance and adequately managing your dopaminergic system, you can improve your likelihood of achieving your goals and find more fulfillment in the process along the way.

Sources

- The Molecule of More: How a Single Chemical in Your Brain Drives Love, Sex, and Creativity―and Will Determine the Fate of the Human Race by Daniel Lieberman and Michael Long

- Dopamine Mindset and Drive - Andrew Huberman Youtube Video

- Increase Your Motivation - Andrew Huberman Youtube Video

- UNDERMINING CHILDREN'S INTRINSIC INTEREST WITH EXTRINSIC REWARD by M. LEPPEK, D. GREENE, AND R. NISBETT

- Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson

- The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization by Peter Senge